Today's topic is, in a lot of ways, a very obvious pick for our series on masculinity. I mean, Billy Elliot is, if nothing else, a story that is all about the presentation of masculinity and how compulsory masculinity can be enforced just like compulsory femininity. But we're not going into this by looking at the film version of the story, amazing though that movie is. Instead, I'd like to talk more about the musical adaptation of that film, also named Billy Elliot, because I think that in a small way, the musical manages to capture more fully the tensions at play in the issues of gender performance and class warfare.

I mean, for all that Billy Elliot seems a very straightforward story of "boy wants to do slightly feminine-coded thing, boy's father recoils in horror, father comes to accept son and feminine-coded thing at end", Billy Elliot actually has a whole hell of a lot going on. So let's dive in.

For those of you unfamiliar, the film version of Billy Elliot came out in 2000 and really is amazing. Starring Jamie Bell as the titular character, it follows a young boy named Billy who discovers one day that there is something in this world called ballet and that he wants, more than anything in the world, to be a dancer.

This doesn't go over particularly well with his father, a gruff single-dad trying to raise his two sons during the coal mine strikes of the early 1980s in Britain. His father is out there fighting for their survival, while Billy keeps sneaking off to go play dressup and dance with girls. Nothing could seem more trivial to his dad.

Eventually, though, Billy's father comes around and the town rallies around him, seeing Billy as their one great chance at hope, since (as we know from history) the strike does not end well. At the end, the strike is over and the miners have lost, but Billy gets into a fancy ballet academy and becomes a professional dancer, proving that he can achieve his dreams and living up to the hopes of the people in his town. Awww.

Well, sort of. I should point out that the film is much less sentimental than I just made it sound. In fact, a big part of why I've never covered it before is because the film is actually quite hard for me to watch. It's incredible, make no mistake, but it's so unrelentingly grim that I had trouble making it through the first time, let alone the repeat viewings needed for an analysis like this.

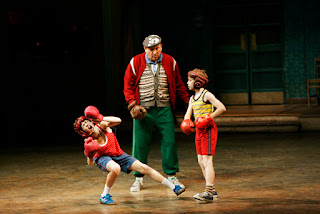

Lucky for me, the musical (which I have seen a few times, actually) is a lot less grim but has the same basic plot. The difference, of course, is that the songs provide a nice break from the sadness and allow you to see Billy in all his dancing glory. So I highly recommend it.

But, like I said above, there really is much more to this story than an obvious analysis of a nice white boy discovering that it's okay to like feminine things. Way, way more.

For starters, the musical and film both make it clear that a big part of compulsory masculinity has to do not just with identity, but with class pride. See, Billy and his family are working class. They're miners, from a mining town, and have been miners since time immemorial. Billy's grandfather, his father, and even his older brother Tony, are or were all miners. It's expected that one day Billy too will take his place in the mine. Not because he's not good for anything else, but because that's just the way it is.

Then you've got the timing of the story. This is taking place right during the mining strikes of the 1980s, when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (called, mockingly, "Maggie" throughout the story) was shutting down the socialized mining system Britain had put into place after WWII. I'm not going to get too much into the economics of it, but suffice to say that the socialized system of mine governance in place was one that was good for the workers - not great, but definitely good - and Thatcher's replacement largely involved shutting down the mines. It's a huge part of why she is still so hated in much of Britain, and why there were people swearing they'd dance on her grave. She literally put a quarter of a million people out of work.

But that was later. This was the beginning of that, when the miner's union thought that they could defeat Thatcher's plan by going on strike. Billy's father and brother are front and center of the strike in their town. Everyone is excited, figuring that the strike will be over by Christmas and that everything will go back to normal because the people, united, will never be defeated.*

In all of this, the Elliots' pride about being working class is a huge part of the story. They don't have any ambition to "rise above their station" - there's even a lyric in the musical that goes "solidary, solidarity / solidarity forever / we're proud to be working class / solidarity forever". The message is pretty clear. This protest is partially about mining rights and the structure of the socialized mining system, but more about the rights of the working class. The rights of "unskilled laborers" (even though we all know that unskilled is more a way of saying that something is messy and physically demanding than actually easy) to determine their own economic futures without the interests of corporations dictating terms.

So, basically, this strike isn't just about the mine, it's about the working class fighting for their place and for respect. When Billy switches from doing boxing to doing ballet, to his family and the town, it's like he's siding with the people they're fighting against. Boxing is a sport for the working classes. Boxing is a good tough "manly" sport, while ballet is something the rich do in their spare time. Right?

The thing is, in a lot of ways this is an accurate assessment. Ballet is something the rich do, because you basically have to be rich to get anywhere with ballet. The lessons are expensive (or at least good lessons are), the clothes aren't cheap either, and you have to travel to performances, take time off of work, go to competitions, take the kid to see other people perform, and more. It's a huge commitment if you want to do it at all well, like any sport, but with the addition of everything being about four times more expensive than you're expecting.

Seriously. I did ballet for four years when I was little, before it became abundantly clear that enthusiasm is no actual substitute for any modicum of talent, and I remember even as a child knowing that it was putting a financial burden on my family. It's just a reality of the art, and one that ought to change.

Billy picking ballet of all things to fall in love with must have felt like the greatest betrayal. Not only is he wanting to be a dancer of all things, he wants to be a dancer in the kind of dance that Maggie Thatcher might attend. It's an outrage, and everyone reacts accordingly.

This is what I mean about the analysis being slightly deeper than you might immediately suspect. Because there is definitely a strong thread of just plain sexism at work here, but there's also classism, and the two are so intertwined as to be inextricable. That's important to remember, because what Billy Elliot is reflecting here is true. Class and gender expression very frequently go together, and to go against one is to go against another. But more on that another time.

First, there's the fact that his lower class family is a single-parent household. Billy's mother died several years ago, and he is raised by his father and older brother. His grandmother is still around and lives with them, but she has a mild case of dementia and he spends more time caring for her than vice versa. Billy's father clearly loves his son, but he also clearly doesn't think much about him at the beginning of the story. Jackie - that's his father's name - is more concerned with the strike and keeping his sons in line than with worrying about their hopes and desires. His father is just plain busy, so a lot of the problem comes from a form of benign neglect that is all too common in working class single-parent households.

Interestingly, though, the story does take time to establish that the men in Billy's family have a history of being good dancers. At one point Billy's grandmother tells him a story about his grandfather. It's not a particularly flattering story, to be sure, but it is interesting. See, apparently Billy's grandfather was a drunken, abusive bastard, but he was also a divine dancer. His grandmother's fondest memories of them were when they would go out drinking and dancing. And by fondest memories, I mean only fond memories.

What's really interesting here is that his grandmother openly states that if she had the chance to do it all over again, she wouldn't. She would do literally anything else. She'd go dancing on her own, get drunk, do what she wanted, whatever, she just wouldn't get married to that drunken lout. It's a fascinating (and honest) thing for her to say, but it underscores the idea that men being told they are naturally rough and violent and "hard" is bad for both men and women. And the idea that under all of that Billy's grandfather was a great dancer raises the question of why, exactly, he was so miserable in all other areas of his life.

Anyway, that's more of a sidenote than anything else. I just find it really fascinating to see a story like this where the effects of compulsory masculinity are explored so deeply.

They're also not just examined in terms of Billy, but also in terms of his best friend, Michael. Michael is a lot of people's favorite character in the film, and it's not hard to see why. He's funny and charming and a complete drama queen. He dresses up in his sister's clothes in his spare time, but calls Billy a weirdo for liking ballet. Eventually we find out that Michael is (probably) gay - but at no point does the narrative say that all this makes Michael less manly. Because it doesn't.

Adding in Michael's simultaneous exploration of gender performance makes Billy's feel more normal. Billy's not doing ballet because he's rebelling or he's gay or because he doesn't have a mother. He's just doing it because he likes it and he doesn't need a better reason. And as far as his sexuality goes, while everyone in Billy's life seems to think it's a big deal and he needs to be concerned with whether he's gay or not, Billy himself doesn't seem to care at all. Which makes sense. He's twelve, and he's already pretty busy.

It all works together so well. That's what I'm getting at. The class struggles and the gender performance and the issues with Billy's family - they all work together to create a complex understanding of how compulsory masculinity works and how we can dismantle it. Because just like there's nothing wrong with a boy liking something more traditionally for girls, there's nothing wrong with a boy liking something traditionally for boys. That's definitely not a problem.

And there are issues related to class conflict that we need to be aware of when looking at gender expression. The key, this story seems to suggest, is that rejection of compulsory masculinity does not mean rejection of your culture and your history. Rejecting being a miner doesn't mean rejecting everyone who chose to be a miner or the history of your family or your love for your town. You can have both. You can have ballet and you can also be up front about being from a working class family in a coal mining town.

That's the key, I think. Finding a way to decouple the ideas of cultural history from gender expression. But it's still a conversation that needs to be had.

One final closing note: I mentioned at the very beginning that I think Billy Elliot the musical is ever so slightly more interesting an examination of this topic than Billy Elliot the film, and here's why: it's to do with the actors. In a film, it's easy to forget that the characters you're watching aren't real, and these aren't actual coal miners, they're paid actors playing pretend. It is virtually impossible in watching a stage production, which is very interesting.

When you're watching Jackie and Tony sing about being worried about Billy getting involved with stage people, or talk about how they don't believe in the arts, or rail that no one who loves dancing can be a real man, you're forced to confront that they're doing this while singing and dancing. There's just this added level of cognitive dissonance that makes it really really complex and cool.

Billy Elliot has a whole hell of a lot to say about compulsory gendering and gender expression - and it doesn't hurt that the music is pretty damn good too.

*Which is probably my favorite protest chant ever, even if it is rather provably untrue.

No comments:

Post a Comment