What

is our cultural emotional thing about princesses and dragons? Seriously, what is it? They each make sense on their own, what with people discovering dinosaur bones and lacking the context in which to understand them as fossils instead imagining them as giant fire breathing lizards, and what with people always seeming to be obsessed with young women whose fathers are of high social standing. I get dragons, and I get princesses. But why princesses and dragons?

I'm sure you all could tell me the story. It's about this princess - she's beautiful of course, because they're always beautiful - and her parents love her very much. She's the perfect princess, all sweet and nice and kind and did I mention beautiful? Because that's the highest virtue a woman can have. Her beauty.

Anyway, this princess is universally beloved because blah blah blah, until one evil day the kingdom is attacked by an evil dragon. This dragon, who is generally without specified gender or purpose, destroys a huge part of the kingdom and castle before flying off with the princess in its clutches. Weirdly, the princess is not hurt or killed by being picked up in the claws of a giant flying lizard and then carried for miles somehow without being dropped or impaled by talons.

The king and queen (if there is a queen - she might have died for dramatic effect) beg the people to help them. Find us a prince! Find us a prince who can go slay the dragon and rescue the princess!

The princess must wait years in the dragon's lair, or in the helpfully provided and inexplicable tower that the dragon has thoughtfully prepared for her. Finally, though, her dreams come true, and a handsome prince - they're always handsome - comes to rescue her. He fights the dragon, and even though an entire army couldn't kill the thing the first time, this one prince manages to kill it with his sword. He saves her, and she is his. His prize. Because even though they've literally never seen each other before in their lives, she is automatically his property once the dragon is dead and they get married and presumably have lots of babies in order to secure the line of succession for both of their kingdoms, thus perpetuating a system of inequality and unsustainable economic oppression for the proletariate.

Sorry. Got distracted.

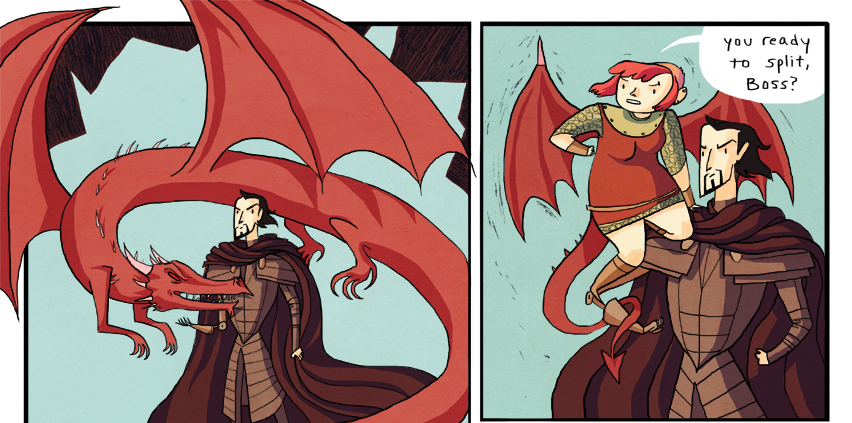

I want to talk today about a very different story. This story,

Nimona by Noelle Stevenson, is the rare story where the princess

is the dragon, and frankly, it's a lot more interesting than what we're used to hearing.

But before we begin, some background.

Nimona started out as Stevenson's art school project. She was tasked with coming up with some original characters to draw, and a joke with a friend had her coming up with the idea of "monkpunk", or a medieval world with improbable mad science mixed in. Laser guns

and knights in armor. The idea spiraled and out of it came

Nimona, a webcomic still available for free online, but that will also be published in full form (with additional content) May 2015 by HarperCollins.

It's one of the great internet success stories of a good project getting the person who made it enough recognition for everyone else to see how dang talented they are. Noelle Stevenson started out as an art student with a weird project, and now that project is getting published while she works as a very much in demand comics artist and writer. She helped create and now writes the awesome comic

Lumberjanes, does a special back page in

Sleepy Hollow, and starting next year will be working for Marvel on the revamped

Thor. So, yeah, I think it's worked out well for her. Which is awesome.

The comic itself is, however, our main point of discussion today. Here's how Stevenson describes it:

Lord Ballister Blackheart has a point to make, and his point is that the good guys aren't as good as they seem. He makes a comfortable living as a supervillain, but never really seems to accomplish much - until he takes on a new sidekick, Nimona, a shapeshifter with her own ideas of how things should be done. Unfortunately, most of those ideas involve blowing things up. Now Ballister must teach his young protégé some restraint and try to keep her from destroying everything, while simultaneously attempting to expose the dark dealings of those who claim to be the protectors of the kingdom - including his former best friend turned nemesis, Ambrosius Goldenloin. [x]

Here's what I have to add to that: The story is madcap, fun, and a little loose on the plotting. It's good, don't get me wrong, but there are big stretches that feel like filler, and sometimes it's hard to tell how it's all going to tie together. I'm very curious to read it in the final form in the book, to see if any of the additional content adds to the emotions of the story or not. But, in general, the story of the comic is solid and interesting.

The story is told from the perspective of Ballister Blackheart, but it's really

about Nimona. Nimona who just randomly shows up one day and badgers Ballister until he lets her be his sidekick. Why? Well, it's hard to say without spoiling it, but suffice to say that she does have a reason, and it's a good one. Nimona's a shapeshifter, with a strong predilection for the more violent and untamable forms. She can turn into a dragon, a shark, a wolf, and she does.

Mostly she uses her powers for good. Sort of. Ballister is officially a supervillain, but the story is a lot like

Dr. Horrible in that Ballister isn't the bad guy. He's not sanctioned by the government, but he has no beef with the people. His fight is with the Institution, a shady para-military organization that maimed him, stole his best friend, and is just generally super shady. Also he used to work for them.

He thinks of himself as a crusader against the Institution and for the people. One of those people? Nimona, who, because of her shapeshifting ability, is someone the Institution would very much like to get their hands on. Which would probably be a bad thing.

But what makes the story really compelling, at least for me, is who Nimona is in all of this. Because in this story, Nimona is literally both the princess (okay, technically not a princess as she is not of royal blood, but go with it)

and the dragon. She has a duality of personality and literal physical form that makes her a manifestation of this trope. There comes a point in the story where Nimona is both a little girl in need of being rescued, and the fire breathing dragon the girl needs rescuing from.

My head hurts just thinking about it.

And yet I can't

stop thinking about it. I mean, dang, that's deep. Nimona is the dragon and the damsel all wrapped into one. She is the thing that she most fears, and she is also the thing with the most capacity to destroy herself. She's just...it's really cool, okay?

It's an idea that I love and that I can't get out of my head because it's so

true. When it comes to human nature, and that's what those stories about princesses and dragons are ultimately about, it's hard to remember that we are actually ourselves the containers of the things we fear most. As much as we want to blame our circumstances on external forces, like dragons, we have to remember that we have ownership of our lives and ourselves. In other words, your demons or dragons or whatever are

yours. You own them. The dragons are you just as much as the rest of you is.

I know that's weird and deep and confusing, but that's what I love about this comic. It makes me think weird and deep and confusing things. It makes me think about the places in my life that I've chosen to be a damsel instead of a dragon, or a dragon instead of a damsel, and it makes me wonder, how do I be both? Is that possible? Is that something worth wanting?

I've never really understood our cultural fascination on dragons kidnapping princesses, but weirdly this webcomic about a foul-mouthed, foul-tempered little girl who can literally turn into a fire breathing dragon helps me get it. It's about conflict and the battle between good and evil in all of us. And, most importantly, it's about realizing that you, in fact, are the one in control of your own heart. So what are you going to do with it?

|

| Also it's very funny. |