Back in grad school, all those ages and ages (about three years) ago, my friends and I liked to talk a lot about the apocalypse and what we would do if an apocalyptic event were to hit. Part of this was because, as grad students studying movies and television, we watched a lot of movies about this stuff, and another part was because we were all at that time living in Los Angeles, which is particularly bad place to be in case of emergency.

But I think the main reason we talked about it so much, and we really did, was because we never really came to a satisfying conclusion on the subject. We always fell into three separate camps. There was camp "I hope I just die immediately and then don't have to worry about it," and camp "I've got this you guys, no seriously, I am so ready," and camp "Isn't this kind of morbid? We should talk about something else."

Personally, I wavered between the second and third camps, always trying to figure out if I was one of those people utterly convinced of my ability to live in terrible situations, or if I thought considering the concept of mass slaughter was a little icky. In my mind, though, I guess I always thought of myself as the hero of the story. We all do. I imagined the end of the world coming, and I figured that I would be that one character who gets to live to the end, scarred but relatively untouched by all the horror, who escapes out into the world and lives happily ever after in a sanctuary in the wilderness.

I bring this up because now, in light of having seen Snowpiercer, I think I need to add a new category to that discussion. I still don't want to die immediately, but I am no longer comfortable banking on my own survival. More than that, though, I've gotten past the part of myself where I think this a morbid and icky question to ask. I mean, it is. It is morbid and icky. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't ask the question. What it actually means is that we must. And we must ask it now.

Snowpiercer is a dystopian sci-fi movie from the awesome South Korean director Bong Joon-ho (he did The Host and Mother), based on a French comic from the 1980s. The premise of the film, which is very high-concept and honestly bizarre, is that our attempts to fight global warming have brought on a new ice age. All life on Earth has frozen to death, except for a thousand survivors or so, all trapped on a single train that perpetually circles the planet, sustaining the population inside and presumably waiting for the day when it's safe to go outside. But not so much that last part.

The movie itself takes place seventeen years after the planet froze, which means that the main characters of the film have been living on a train for almost two decades. The train itself isn't just one big party, either. It functions as a microcosm of the world: in the front, you have the first class tickets, who live in luxury and excess. Then, the economy class, who work for the first class passengers and go about their lives further back. Finally, in the very tail of the train, with the least space and the worst conditions, are the freeloaders, who have no tickets, and live in less-than-third-world squalor.

These are our heroes.

It's clear from the first ten minutes or so that the conditions in the tail, where everyone is grimy and grubby, covered in matted filth and struggling to keep warm, are horrific, even when compared with the literal unseen. We have no idea what the rest of the train looks like, but we know it must be better than this. At the very least, the soldiers and officials who come back every once are clean.

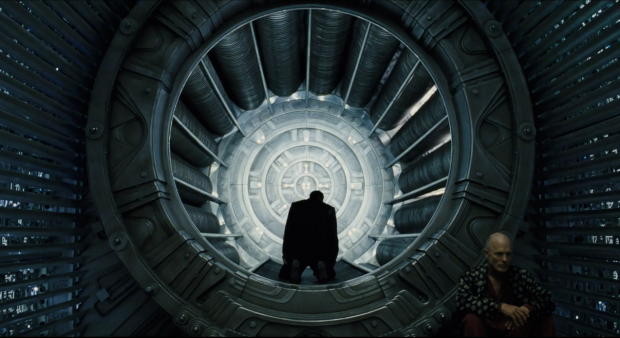

So it's not hard to put it down to class envy that the tail passengers are fomenting revolt. Led by Curtis (Chris Evans) and Gilliam (John Hurt), the tail section is getting ready to fight their oppressors and make their way to the front of the train, fighting to take the engine and seize power. As Curtis says, "If we control the engine, we control the world."

But it's more complicated than just class jealousy. I mean, the tail passengers assume that the people in the front must have it better than they do (because they certainly can't have it worse), but the real reason they're getting ready to revolt is quite simple. It's for the kids. This visceral and horrifying moment when a woman from the front of the train comes to the tail and, without speaking a word, takes two of their children away. Revolutions have been fought for less, and really it's not a minor thing. The tail passengers aren't people to those in the front. They're animals. They're livestock.

And so the story begins. I'm really not going to go into details about what actually happens, because literally anything I could write would ruin it, but suffice it to say that the story is never dull or lagging, the plot is engrossing and completely captivating, and the cast is incredible. Chris Evans deserves an Oscar for his work on this film, and Tilda Swinton (who plays a sniveling bureaucrat who worships the "sacred engine") and Song Kang-ho (who plays a drug-addled security specialist with his own agenda) also need some critical recognition.

Also it has Octavia Spencer, Jamie Bell, Ed Harris, the aforementioned John Hurt, Ewen Bremmer, Ko Ah-sung, Alison Pill, Luke Pasqualino, and more. Everyone is just acting their butts off in this movie. Everyone. Which does bring us to another point about the movie: it's racially diverse and has pretty solid gender representation. I mean, that only makes sense, since this train is supposed to contain the last of humanity, and humanity is pretty freaking diverse, but still. Also worth noting? The class divisions in the train also include implicit racial divisions, which I think it is interesting.

That, however, is not the main point here. What I really want to talk about in this article is how, coming out of the theater reeling and a bit foggy, feeling like I'd just been hit in the face by a telephone pole, I had to sit down and truly think about my life. What is the cost of my life? What is the cost of my survival? And is it a price I am willing to live with?

The main thrust of the movie, from what I can tell, having now seen it twice, is that whether we know it or not, all of our lives cost something. All of them. There is no such thing as free and simple life. In the world of Snowpiercer, that cost is more apparent, when you see that the front sections can only continue to exist by creating horrible conditions for the tail section and that the tail section can only continue to exist by fighting against those conditions but in the process enduring something even more horrible. And, lest we forget, this whole situation got started because the price for the continued existence of the planet (global warming was threatening to end all life anyway) was the destruction of almost all of it.

There is always a cost, and it is high.

The thing is, we don't often think of the way that this applies to our own lives, but it's true. There is a cost, and it is very very high. There is a visible and visceral cost to my continued existence. Parts of it are simple. I am writing this while wearing clothes that were probably made in less than ideal conditions, overseas and for very little money.

The fabric that comprises my clothes was manufactured in nations that receive very little monetary benefit for the workers and traditionally have absolutely terrible stances on workers' rights. The cotton was grown somewhere. What river was diverted to water it? What happened to the farmers whose farms no longer get water now that it's gone to grow cotton for my dress? What about their crops, their families, their lives?

What about the fact that my toilet is filled with clean, potable water every time I flush it, while literal billions have no clean water to drink? I am fortunate to live in a place where water is anything but scarce, but that's rare. And what about the millions of indigenous people who died so that my family could escape persecution and come to this country? There is a cost, is what I'm saying. And it is high.

I don't want to pay that cost, I really don't, but I also don't want to push it off onto someone else. When I think about these things, about the fact that my continued existence relies on the misfortune of so many, and that while there are things I can do to mitigate that, they will never be able to fully fix it, I feel like crying. I feel like crying a lot, actually. Because I don't know what to do.

After I watched the movie, my friend and I went shopping. We both felt a bit weird about it, but I don't go to the mall often and I needed a new pair of leggings and to look for a nice dress for a friend's wedding. So after watching a searing indictment of the class system, I got out of my cushioned chair, walked out into an air-conditioned, beautifully lit mall, and proceeded to buy a dress. It was on sale. I feel sick.

But that's what we do, isn't it? That's how we live with the cost. We ignore it and shove over it and pretend we can't see. Pretend that it doesn't matter, and that we aren't the problem. The little bit that I'm doing? It's enough. It's good. It covers me.

It doesn't cover me. It's not enough.

Here's the thing, though. Just because it's not enough and I can't pay this price even if I wanted to, that's not an excuse. No, I can't win. But that is no excuse not to try.

Just because we have always lived lives that cost something, and because we have no idea how not to, is no reason to keep on doing it. At some point we absolutely must put our feet down and say, simply, "My life is not worth more than yours. I refuse to live if you cannot." Because, well, it isn't. It really isn't.

As I was watching the movie, I started to think about other stories I know about people who, seemingly at the end of the world, decided that their lives were not worth more than anyone else's, and lived like that. There's Eric Liddell, who went from winning a gold medal in the Olympics to living out his final days in an internment camp in China. When the officials discovered he was an Olympian, they tried to release him, and he refused to go. He asked instead that they let some of the others go in his stead. He stayed there until his death, and he became known as Uncle Eric, the most beloved man there, who kept everyone else alive.

There's Corrie Ten Boom, a Dutch woman who hid Jews in her attic during the German invasion, was caught, and spent the war in a concentration camp. The Jews escaped, and she was grateful. After the war, she bought a concentration camp and turned it into a reconciliation center to help the people of Europe heal. She refused to believe that her life was worth more than her Jewish neighbors', but she also refused to believe that her life was worth more than her Nazi neighbors' as well.

I want to be like that. I want to live with radical selflessness.

I want to be able to know that if the end of the world comes, yes, I might survive, but I will only do so if we can do it together. I want to know that my life costs very little, and that I have done all I can to make it cost less. I want to know that I did not survive because I thought my life more important than someone else, because it isn't. That does not mean my life has no value. It just means that yours does too.

I want to know that if the end came, and I had the choice to fight and survive, or lose my life so that someone else might live, I would take the second option. Yes, that sounds terrible, and no, I don't want that. But I want to want it. I want to understand myself on those terms. I am right with God and set for eternity. I don't want to cling so tightly to this life that I forget how much your life matters too.

The ending of Snowpiercer is a strange one. That's not a spoiler, as the whole movie is strange, but I think it bears mentioning. The movie does not have an easy ending. At the very least, you are forced to reckon with the actions of the characters throughout the film. Was what they did right? Wrong?

Was the cost too high, or was it worth paying? And, ultimately, what cost is too high for us, when we consider how much our lives are worth?

I don't want to close my eyes anymore to the suffering in the world. I don't want to be complacent to the misery of others. I know that I can't change the world myself, but I also know that I have no excuse not to try. So I will.

Also, Snowpiercer is the kind of amazing movie that is destined to be a classic up there with Bladerunner and Metropolis. It's in limited release right now, but I promise you it is worth hunting down to see it in theaters. It will hurt and horrify you. That's a good thing.

But I think the main reason we talked about it so much, and we really did, was because we never really came to a satisfying conclusion on the subject. We always fell into three separate camps. There was camp "I hope I just die immediately and then don't have to worry about it," and camp "I've got this you guys, no seriously, I am so ready," and camp "Isn't this kind of morbid? We should talk about something else."

Personally, I wavered between the second and third camps, always trying to figure out if I was one of those people utterly convinced of my ability to live in terrible situations, or if I thought considering the concept of mass slaughter was a little icky. In my mind, though, I guess I always thought of myself as the hero of the story. We all do. I imagined the end of the world coming, and I figured that I would be that one character who gets to live to the end, scarred but relatively untouched by all the horror, who escapes out into the world and lives happily ever after in a sanctuary in the wilderness.

I bring this up because now, in light of having seen Snowpiercer, I think I need to add a new category to that discussion. I still don't want to die immediately, but I am no longer comfortable banking on my own survival. More than that, though, I've gotten past the part of myself where I think this a morbid and icky question to ask. I mean, it is. It is morbid and icky. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't ask the question. What it actually means is that we must. And we must ask it now.

Snowpiercer is a dystopian sci-fi movie from the awesome South Korean director Bong Joon-ho (he did The Host and Mother), based on a French comic from the 1980s. The premise of the film, which is very high-concept and honestly bizarre, is that our attempts to fight global warming have brought on a new ice age. All life on Earth has frozen to death, except for a thousand survivors or so, all trapped on a single train that perpetually circles the planet, sustaining the population inside and presumably waiting for the day when it's safe to go outside. But not so much that last part.

The movie itself takes place seventeen years after the planet froze, which means that the main characters of the film have been living on a train for almost two decades. The train itself isn't just one big party, either. It functions as a microcosm of the world: in the front, you have the first class tickets, who live in luxury and excess. Then, the economy class, who work for the first class passengers and go about their lives further back. Finally, in the very tail of the train, with the least space and the worst conditions, are the freeloaders, who have no tickets, and live in less-than-third-world squalor.

These are our heroes.

It's clear from the first ten minutes or so that the conditions in the tail, where everyone is grimy and grubby, covered in matted filth and struggling to keep warm, are horrific, even when compared with the literal unseen. We have no idea what the rest of the train looks like, but we know it must be better than this. At the very least, the soldiers and officials who come back every once are clean.

So it's not hard to put it down to class envy that the tail passengers are fomenting revolt. Led by Curtis (Chris Evans) and Gilliam (John Hurt), the tail section is getting ready to fight their oppressors and make their way to the front of the train, fighting to take the engine and seize power. As Curtis says, "If we control the engine, we control the world."

But it's more complicated than just class jealousy. I mean, the tail passengers assume that the people in the front must have it better than they do (because they certainly can't have it worse), but the real reason they're getting ready to revolt is quite simple. It's for the kids. This visceral and horrifying moment when a woman from the front of the train comes to the tail and, without speaking a word, takes two of their children away. Revolutions have been fought for less, and really it's not a minor thing. The tail passengers aren't people to those in the front. They're animals. They're livestock.

And so the story begins. I'm really not going to go into details about what actually happens, because literally anything I could write would ruin it, but suffice it to say that the story is never dull or lagging, the plot is engrossing and completely captivating, and the cast is incredible. Chris Evans deserves an Oscar for his work on this film, and Tilda Swinton (who plays a sniveling bureaucrat who worships the "sacred engine") and Song Kang-ho (who plays a drug-addled security specialist with his own agenda) also need some critical recognition.

Also it has Octavia Spencer, Jamie Bell, Ed Harris, the aforementioned John Hurt, Ewen Bremmer, Ko Ah-sung, Alison Pill, Luke Pasqualino, and more. Everyone is just acting their butts off in this movie. Everyone. Which does bring us to another point about the movie: it's racially diverse and has pretty solid gender representation. I mean, that only makes sense, since this train is supposed to contain the last of humanity, and humanity is pretty freaking diverse, but still. Also worth noting? The class divisions in the train also include implicit racial divisions, which I think it is interesting.

That, however, is not the main point here. What I really want to talk about in this article is how, coming out of the theater reeling and a bit foggy, feeling like I'd just been hit in the face by a telephone pole, I had to sit down and truly think about my life. What is the cost of my life? What is the cost of my survival? And is it a price I am willing to live with?

The main thrust of the movie, from what I can tell, having now seen it twice, is that whether we know it or not, all of our lives cost something. All of them. There is no such thing as free and simple life. In the world of Snowpiercer, that cost is more apparent, when you see that the front sections can only continue to exist by creating horrible conditions for the tail section and that the tail section can only continue to exist by fighting against those conditions but in the process enduring something even more horrible. And, lest we forget, this whole situation got started because the price for the continued existence of the planet (global warming was threatening to end all life anyway) was the destruction of almost all of it.

There is always a cost, and it is high.

The thing is, we don't often think of the way that this applies to our own lives, but it's true. There is a cost, and it is very very high. There is a visible and visceral cost to my continued existence. Parts of it are simple. I am writing this while wearing clothes that were probably made in less than ideal conditions, overseas and for very little money.

The fabric that comprises my clothes was manufactured in nations that receive very little monetary benefit for the workers and traditionally have absolutely terrible stances on workers' rights. The cotton was grown somewhere. What river was diverted to water it? What happened to the farmers whose farms no longer get water now that it's gone to grow cotton for my dress? What about their crops, their families, their lives?

What about the fact that my toilet is filled with clean, potable water every time I flush it, while literal billions have no clean water to drink? I am fortunate to live in a place where water is anything but scarce, but that's rare. And what about the millions of indigenous people who died so that my family could escape persecution and come to this country? There is a cost, is what I'm saying. And it is high.

I don't want to pay that cost, I really don't, but I also don't want to push it off onto someone else. When I think about these things, about the fact that my continued existence relies on the misfortune of so many, and that while there are things I can do to mitigate that, they will never be able to fully fix it, I feel like crying. I feel like crying a lot, actually. Because I don't know what to do.

After I watched the movie, my friend and I went shopping. We both felt a bit weird about it, but I don't go to the mall often and I needed a new pair of leggings and to look for a nice dress for a friend's wedding. So after watching a searing indictment of the class system, I got out of my cushioned chair, walked out into an air-conditioned, beautifully lit mall, and proceeded to buy a dress. It was on sale. I feel sick.

But that's what we do, isn't it? That's how we live with the cost. We ignore it and shove over it and pretend we can't see. Pretend that it doesn't matter, and that we aren't the problem. The little bit that I'm doing? It's enough. It's good. It covers me.

It doesn't cover me. It's not enough.

Here's the thing, though. Just because it's not enough and I can't pay this price even if I wanted to, that's not an excuse. No, I can't win. But that is no excuse not to try.

Just because we have always lived lives that cost something, and because we have no idea how not to, is no reason to keep on doing it. At some point we absolutely must put our feet down and say, simply, "My life is not worth more than yours. I refuse to live if you cannot." Because, well, it isn't. It really isn't.

As I was watching the movie, I started to think about other stories I know about people who, seemingly at the end of the world, decided that their lives were not worth more than anyone else's, and lived like that. There's Eric Liddell, who went from winning a gold medal in the Olympics to living out his final days in an internment camp in China. When the officials discovered he was an Olympian, they tried to release him, and he refused to go. He asked instead that they let some of the others go in his stead. He stayed there until his death, and he became known as Uncle Eric, the most beloved man there, who kept everyone else alive.

There's Corrie Ten Boom, a Dutch woman who hid Jews in her attic during the German invasion, was caught, and spent the war in a concentration camp. The Jews escaped, and she was grateful. After the war, she bought a concentration camp and turned it into a reconciliation center to help the people of Europe heal. She refused to believe that her life was worth more than her Jewish neighbors', but she also refused to believe that her life was worth more than her Nazi neighbors' as well.

I want to be like that. I want to live with radical selflessness.

I want to be able to know that if the end of the world comes, yes, I might survive, but I will only do so if we can do it together. I want to know that my life costs very little, and that I have done all I can to make it cost less. I want to know that I did not survive because I thought my life more important than someone else, because it isn't. That does not mean my life has no value. It just means that yours does too.

I want to know that if the end came, and I had the choice to fight and survive, or lose my life so that someone else might live, I would take the second option. Yes, that sounds terrible, and no, I don't want that. But I want to want it. I want to understand myself on those terms. I am right with God and set for eternity. I don't want to cling so tightly to this life that I forget how much your life matters too.

The ending of Snowpiercer is a strange one. That's not a spoiler, as the whole movie is strange, but I think it bears mentioning. The movie does not have an easy ending. At the very least, you are forced to reckon with the actions of the characters throughout the film. Was what they did right? Wrong?

Was the cost too high, or was it worth paying? And, ultimately, what cost is too high for us, when we consider how much our lives are worth?

I don't want to close my eyes anymore to the suffering in the world. I don't want to be complacent to the misery of others. I know that I can't change the world myself, but I also know that I have no excuse not to try. So I will.

Also, Snowpiercer is the kind of amazing movie that is destined to be a classic up there with Bladerunner and Metropolis. It's in limited release right now, but I promise you it is worth hunting down to see it in theaters. It will hurt and horrify you. That's a good thing.

I think the point of the ending is that a system that requires this much exploitation isn't worth continuing.

ReplyDelete"There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part! You can't even passively take part! And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels…upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop! And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!"

Engine and Machine are pretty lasting metaphors. Blake's "Jerusalem", another call to revolution, also references "dark satanic mills."

Spoiler-ish:

No lame, tacked on romance!

To me, one of the more interesting and trope breaking aspects was it wasn't the white guy who was the visionary who saved the day. He was a hero in rejecting his privilege and following the lead of a person of color in rejecting the present for an uncertain future. That to me is what Bong is calling for in the movie, revolution.

I salute this entire post.

ReplyDeleteI know what you mean - one of my biggest struggles as a privileged white western woman is being aware of my privilege and not knowing how to give it up in a way that actually changes anything. Maybe I think too big, I don't know. Maybe it's not about taking the engine, but just saving the one kid, but then which one? and When? It keeps me up at night sometimes.

Including Mayan prescience to a dangerous atmospheric devation and financial fall being sensationalized in the media nowadays, fiasco readiness has turned into a consistently expanding worry for individuals in America and past. survival items

ReplyDeleteThanks for the blog loaded with so many information. Stopping by your blog helped me to get what I was looking for. heirloom vegetables

ReplyDeleteThis is a kind of cleaning as it slaughters all pathogens however doesn't dispose of particles. Water ought to be kept at a moving bubble for at any rate 1 moment to disinfect it.

ReplyDeleteread this

KOLKATA HOUSEWIFE ESCORT SERVICE

ReplyDeleteKOLKATA BOUDHI ESCORTS

INDEPENDNET ESCORT IN KOLKATA

KOLKATA ESCORT AGENCY

RUSSIAN ESCORT

RUSSIAN ESCORTS

RUSSIAN CALL GIRL

RUSSIAN CALL GIRLS

HOUSEWIFE ESCORT

HOUSEWIFE ESCORTS

HOUSEWIFE CALL GIRLS

HOUSEWIFE CALL GIRL

MODEL ESCORT

MODEL ESCORTS

COLLEGE CALL GIRL

COLLEGE CALL GIRLS

INDEPENDENT ESCORT SERVICE

INDEPENDENT ESCORTS SERVICE

INDEPENDENT ESCORTS SERVICES

INDEPENDENT CALL GIRL

INDEPENDENT CALL GIRLS

ESCORT

ESCORTS

FEMALE ESCORTS SERVICE KOLKATA

KOLKATA FEMALE ESCORTS SERVICE

INDEPENDENT ESCORTS SERVICE

INDEPENDENT ESCOTRTS SERVIC KOLKATA

KOLKATA INDEPENDET ESCORTS SERVICE

RUSSIAN ESCORTS SERVICE KOLKATA

RUSSIAN ESCORTS SERVICE

KOLKATA RUSSIAN ESCORTS SERVICE

FOREIGN ESCORTS SERVICE IN KOLKATA

INDEPENDEN FOREIGN ESCORTS SERVICE

ESCORT FOREIGN SERVICE IN KOLKATA