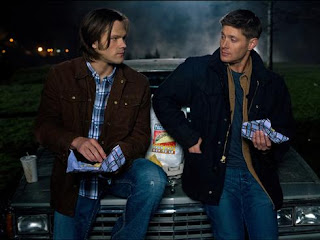

If you’ve ever seen the very first episode of Supernatural, you know that the show

didn’t actually start out with the boys together. Instead, Sam was at Stanford,

trying to forget he had a family, and Dean was out hunting, trying to remember

how to be someone without his family. Neither of them were succeeding very

well. So, Dean went to see Sam and convinced him to come along on the hunt for

their father.

In so doing, he used this line: “Sam, I can’t do this alone.”

To which Sam replied, “Yeah you can.”

And Dean came back with this: “Yeah, well, maybe I don’t

want to.”

I think this is a lot more important than we think. You see,

Dean isn’t just saying that he likes Sam, or that he thinks it’s nice when Sam

is around. He isn’t going to him with an obligation, either. Well, he is, but

that’s not the heart of it. Nor is he incapable of doing the work should Sam

refuse. It’s none of that. It is simply that Dean doesn’t want to do it alone.

He wants to do it with Sam.

We see this a lot in popular culture. A lot. But I don’t

think we often look at the heart of it. It underpins some of our most popular

cult shows, and gets to the core of who we are as people. It is not good to be

wholly alone. Community is important.

Look at Buffy the

Vampire Slayer. Now, when you look at the show, it’s pretty freaking

obvious who the star is. She’s the one with her name in the title. She has

superpowers. She can kill monsters. But, she’s not alone. She has help. Maybe

her help isn’t nearly as good at the monster slaying as she is, maybe they get

kidnapped a lot and complain and sometimes make her tear her hair out, but

they’re there because she wants them around. Because it is better to do it

together.

And this gets spotlighted in season three. There we meet

Faith, another slayer, also with superpowers and snarkiness, and really

hilariously bad fashion sense (was that like a part and parcel of the slayer

package or something?). Faith is alone. Wholly, utterly alone. She doesn’t even

have a Watcher, let alone any friends.

And Faith wants. She yearns for what Buffy has. She falls

into darkness and bad relationships because she feels so incredibly alone.

It is not good to be alone. We desire community.

But it’s not just us. We sad little humans aren’t the only

ones who desire community. Even stories about aliens as powerful as gods, like Doctor Who, maintain this principle.

When the Doctor regenerates, the first thing he does is look for someone to

share in his adventures with him. He has no desire to go alone. Alone is bad.

Sometimes, of course, we lose sight of that. We believe that

only by being alone can we protect those we love. But that’s crap. Without

relationships and messy human emotions, there’s nothing worth protecting. The people

we love are the ones who make it all worthwhile.

This is why, I believe, we love stories about werewolves,

who are instantly members of a pack that will defend each other to the death.

Why we adore sitcoms about friends who are closer than family to each other,

and why we obsess over deep relationships like John and Sherlock, or Arthur and

Merlin, or Xena and Gabrielle. We love the idea of people who will never leave

us. Never leave us alone.

And this is why stories about people who are alone,

tragically alone, are so heartwrenching to us. Recently I’ve been watching the

BBC drama Luther, which is fabulous

and I’ll surely have more to say on it soon, and I can say that John Luther

does not like being alone. That’s part of what gives the show its kick.

He is

searching constantly for someone who can understand him and his drive, and to

that end he befriends the most unlikely of people, chases after his former

wife, and takes unreasonably risks. The lack of human companionship in his life

has made him rather literally crazy.

But what does all of this mean? What does it matter?

I firmly believe that looking at stories critically and

analytically is the best way to understand who we are as human beings. The

stories we tell ourselves, to frighten away the dark, or to keep warm, or just to

entertain, reflect our values and our desires.

And clearly we desire community. Lots of it.

Why then, are we so alone?

If we strongly desire to be with other people, why do so

freaking many of us state that we feel depressed or lonely or abandoned?

Because even though we know that alone is bad, we are way too awkward to do

something about it. And that is terrible.

We’re too uncomfortable, too sheltered, too ensconced in our

own warm cozy worlds to reach out and try to connect with the person sitting

across from us in the café. We don’t want to be weird. We really don’t want to

be that guy. But by being afraid of

public opinion, we lose the opportunity to matter. When we don’t reach out, we

imply that the possibility of scorn is more important than the probability of

friendship.

And that, my friends, is a terrible way to live.

So the next time you’re hanging out somewhere, and you see a

stranger who looks a bit lost and adrift, or you happen to notice someone who

is sad, or lonely, or just bored, pull a Doctor. Go up to them, reach out a

hand, and say, “Would you like to go on an adventure?”

|

| Because alone is not pretty. |

This is why, I believe, we love stories about werewolves, who are instantly members of a pack that will defend each other to the death.

ReplyDeleteAnd maybe why we're liable to defend even the most monstrous of vampires as tragic figures in need of romance (like True Blood's Franklin Mott being considered a serious love interest for Tara).

Okay, I do have to confess that I don't watch True Blood, and therefore don't get that reference, but I do think that our discomfort with the lonely hunter does get translated to vampires. Both in a need to see them redeemed and in community, and in stories about vampire clans and things like the Cullens, where they enjoy perfect community and family. It's very interesting.

Delete