|

| The less controversial cover. |

Okay, massive disclaimer here. If you are reading this

article at work, on the subway, or generally anywhere that someone might look

over your shoulder and be a bit miffed by an interesting topic, you should

probably stop now and resume reading once you’re in the comfort of your own

home.

Just saying.

Are they gone? Good. Let’s get started.

A couple of recent controversies have brought to light a

very interesting double standard in our culture. Namely, that we find

breastfeeding to be an objectionable action and scandalous or even perverse to

do and be seen doing in public, but we don’t have nearly the same problem with

bared breasts in general. And this is a bit weird.

The scandals I’m referring to here are actually pretty

numerous. First, there’s the scandal around that Time Magazine cover, you know, the one with the kid and his mom and

the strategically placed chair. People were utterly scandalized by the cover,

which shows a mother breastfeeding her toddler son. It was obscene, you heard

some people say, while other, more sensible people were merely offended by the

article’s title, “Are You Mom Enough”, which is just dumb.

Then there’s the way that Facebook has adopted a policy of

yanking any and all pictures of breastfeeding, citing them as pornographic

works. It does not, however, automatically take down images of young girls with

their hands covering their nipples, which seems a bit odd since those actually

are intended as pornographic works.

Let’s not leave popular culture out of this either! Game of Thrones featured an entire scene

about the ickiness of attachment parenting gone wrong, which was intended to

squick the audience, and did it so well that it spawned a real life controversy

about the actors involved. Or we could talk about the recent issues with the

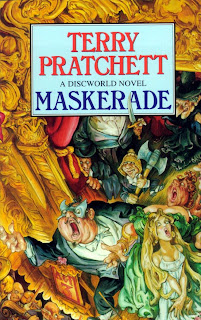

cover of Saga Issue 1, which features

breastfeeding (and interspecies marriage).

|

| Okay, to be fair, this scene was just weird. |

Why are we so uptight about this? What is it about

breastfeeding that makes us all phenomenally flip our wigs?

I have a few theories.

First of all, images of breastfeeding are an intersection of

the sexual and biological functions of the female breast. While we all

(hopefully) know that breasts are designed to be used for the nurture of the

young of our species, hence the mammary gland and the term mammal being

inexplicably related, as a culture we value breasts as sexual features first

and foremost. They are the secondary sexual characteristics so fetishized that

it’s hard to watch anything on television or in any commercial without some

reference to them.

We like boobs, apparently. So much so that any image of a

breast is deemed pornographic and sexual. You hear a lot of stories about young

boys seeing their first images of breasts in National Geographic magazines and being mystified by them. Or of

people discovering Greek and Roman statuary and being transfixed by all the

titties.

Because as a culture we have fetishized the female breast,

we find it very uncomfortable to see images of them in any situation. Our

fetishization of breasts causes us to stigmatize them. If breasts are out, then

clearly it is a sexual situation. Breasts are only sexual and cannot be

neutral.

This is, of course, patently untrue. Breasts are neutral, as

is any human characteristic when removed from a sexual situation. Penises are

for peeing much more than they are for sex. Vaginas may be a sexual orifice,

but they also connect to the urethra, and about a quarter of the time they

aren’t very fun anyways, trust me. Breasts happen to be where the milk comes

from for babies. While it is a product of sex, it’s not sex itself. Sorry.

It’s just, when we spend all that time and energy obsessing

over and lusting after and being shocked by breasts sexually, it’s incredibly hard

to stop seeing them as demon bazongas, and start seeing them for what they are

in this case, a really squashy vending machine. The fact that some people have

turned lactation into a kink of its own really doesn’t help here.

But here’s what really chafes my butt. The people

complaining about the obscenity of breastfeeding are the same ones arguing

about the oversexualization of our culture. They fail to realize that by

insisting on sexualizing a non-sexual act, they are the creators of this

hyper-sexual culture. By seeing breasts and dirty and wrong when they’re

feeding babies, they create a culture where no breast is ever right.

Breasts are breasts are breasts. Some breasts are

sexualized, some feed babies, and sometimes those breasts are the same breasts.

I mean, babies do come from sex, let’s not all forget that.

The important thing in the breastfeeding debate is that

people seem to have forgotten the importance of context. A breast exposed

during sex is intended to have a

different reaction than a breast revealed in feeding. The intended response and

the situation in which the baring occurs are what should determine our reaction

to it.

Now, I’m not saying that women should be stripping down all

over the place willy nilly here. It’s winter and that would be cold.

What I am saying is that we all need to chill out and take a

second to examine our motives. Why are we offended by images of breastfeeding?

I think you’ll find that in most cases, we’re only really offended by it

because we’re afraid of it. And we’re only afraid of it because we’ve given the

idea of the breast way, way too much power.

Of course, I did say that there would be multiple theories,

so here are a few more:

All women are actually fem-bots from Austin Powers and their breasts conceal tiny guns.

Seeing an uncovered breast will make you go blind.

Incidentally, all women are blind.

Breasts know kung fu. They’re waiting for you to look at

them so they can throw the baby aside and judo chop you into next week.

Everyone is secretly a twelve year-old boy, and breasts are terrifying.

But really guys, when it comes down to it, boobs aren’t that

scary. They aren’t that sexual either. What they are is just a part of the

human body to which we have assigned cultural significance. We decided that all

breasts are sexual. And we’re wrong.

|

| Apparently this is scandalous. Yeah, no. |