When you’re writing a television pilot, generally speaking

you have a protagonist (usually male, but that’s evening out) who has an

undefined goal in life and will be shaken out of his doldrums into the wacky

world of your story. If you’re going to do that, then the easiest way is with

The Girl. That’s right, just introduce your guy to a girl character who

represents everything that he actually wants, and this will force him to grow

and advance the plot.

I hate it when they do this.

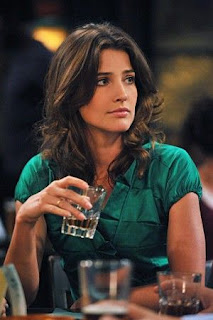

In the pilot episodes of both Community and How I Met Your

Mother, our straight white male protagonist isn’t spurred into action until

he meets The Girl. She is the perfect girl for him. Pretty, unattainable,

interested in the same stuff he is.

Utterly lacking in her own personality.

On Community, the

influential girl was of course Britta. In the very first episode we see that

Jeff starts the study group so that he can have an excuse to hang out with her.

Which is fine, there are much worse reasons to do things, but it leaves the

show a little bereft. You see, Jeff does things because he wants Britta to

notice him. The story, though, doesn’t give any validity to Britta’s side. We

are entirely in Jeff’s pocket, and Britta doesn’t exist as a person. She is a

thing to be won.

It’s not until the later episodes, when Britta starts really

filling out as a character (and a damn funny one at that) that we start to

actually get an idea of who she is. Upon first glance, Britta is just an

amalgamation of all the things that Jeff finds attractive. She’s The Girl. She

doesn’t have a role in the story of her own, she’s just there to move the plot

along and be the carrot dangling in front of our main character, spurring him

on.

In How I Met Your

Mother, it’s even more pronounced. Unlike Jeff Winger, who is a confirmed

womanizer and proud of it, Ted sees himself as a sensitive guy. When he sees

Robin across the bar in the pilot episode, he knows that he wants to get to

know her. To date her. Maybe even to marry her. Which is ridiculous because he

has literally never spoken to her. At least Jeff is honest about how little he

really cares for Britta’s feelings at first. In the pilot, Ted treats Robin

like some magical being created just for him, despite not knowing her at all

and professing to be a nice guy.

It’s not until later in the first season, and then the

second, when we actually get to know Robin as more than just that chick Ted

wants to bang. It’s when she actually suits up to have bourbon with Barney, or

when we find out about Robin Sparkles, or the later episode when we find out

she was raised as a boy. Until we find out Robin’s quirky little flaws, she’s

not a person. She’s an object. Just another thing Ted thinks he needs to feel

complete.

And, ultimately, that’s the problem with “The Girl”. She’s

not a real character, she’s a level. It’s lazy writing, assuming that all our

hero needs to be inspired or to be complete is a girl. It gives said girl no

agency, and just assumes that she’ll be happy playing in to the male

protagonist’s fantasy.

As the years go on, this actually becoming more prevalent in

female lead shows as well. I mean, it’s equality, but really? Not what we want.

In the first episode of Heart

of Dixie, Zoe spies a cute guy, talks to him, and decides to stay. Said

cute guy really has no personality for most of the first season. Or in Grey’s Anatomy, where McDreamy exists

just as a fantasy to all the female characters. I think. I don’t actually watch

that show. It seems nice?

Anyway, creating a character whose sole existence is just to

jolt your protagonist out of his doldrums is annoying and bad. That should be

pretty self-evident.

But the reason I’m still talking about it is because those

two shows up above (Community and How

I Met Your Mother) managed to pull it off. And they did it by developing

the shit out of those characters once they got going.

Look, writing is hard. Sometimes you make shortcuts. I don’t

think anyone here is saying that Dan Harmon is a bad writer or that the HIMYM pilot isn’t hilarious and awesome

(at least I’m not saying that), what I’m saying is that those shows succeeded

because they didn’t keep these

characters underdeveloped. Very quickly we learned to view these women as characters

in their own rights. Funny, psychotic, and occasionally violent characters.

If it weren’t for their development, neither show would

actually work. They would bring the whole level down, to have two women who are

just there for the male protagonist’s sake? That would suck. So they aren’t.

They’re there for them.

The bottom line is that if you’re making a piece of art, and

you want it to be good, whether it’s a show or a movie or a book or whatever,

you have to treat all of the characters in it like people. You can’t pick and

choose which ones get to have agency and which ones are just cardboard props

for your lead to react against. The whole thing has to jive. If you want it to

be good, make everyone a character. Not just the easy ones.

And if you’re going to make a comedy, make everyone funny.

|

| I will forever thank HIMYM for giving us Robin Sparkles and the Beaver Song. Never forget. |

In a way it's similar to side-kick syndome that marginalised characters constantly have to deal with. Characters that exist solely to support and serve the lead, they aren't individuals, they aren't characters, they're tools, they're support staff and they're estensions of someone else's story.

ReplyDeleteAnd it's not too far from women in fridges - albeit the fridged are an extreme example of this. Women there to be the inspiring love interest whose life (or death) drives the protagonist on - but they themselves are nothing, irrelevent, place holders even

You make a really good point. I hadn't quite followed this thought through to where it intersects with fridging. But you're right. When the female character is dehumanized to the extent where she has no agency or separate existence, it becomes much easier for a writer to use her death or abuse as another way to influence his protagonist. And that's icky.

Delete