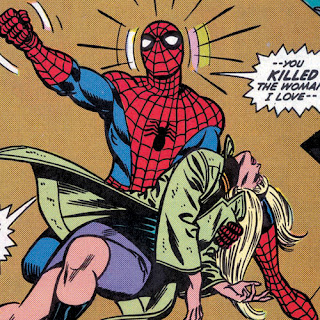

Okay, so today we're going to take a sec and actually look at the comics industry. Specifically, I want to talk about the issue of violence against women in comics.

Because it happens. Kind of a lot. Kind of a disturbing amount.

So let's dive in, shall we?

In Issue #54 of Green Lantern, Kyle Rayner, the titular character (and one of the better Green Lanterns), comes home to find his girlfriend has been murdered and stuffed in his fridge. Understandably, this caused some outrage. But the actual problem I had was simple: I wasn't surprised that there was a dead woman in a fridge.

Someday, I want to be able to introduce my (currently non-existent) daughter to comics. I’m a little bit of a massive geek, and I’d like it to be something we can share. How superheroes are the best versions of ourselves, and they show us what we ought to live up to. How cool it is when you do your best at something you're talented in, and the importance of taking responsibility both for your actions and for the happiness of others. I think this is a good thing.

But if comics don't seriously change in the next however many years until I have that daughter, that's not gonna happen. I refuse to show her the systematic violence and stereotyped behavior that currently runs through superhero comics about women. Because while it seems these days that women are well-represented in comics, in fact, we’re not. I've talked about this a fair amount before, and I think it comes down to one simple thing: writers.

Due to under-representation of female writers, female comics characters rarely have the depth of their male counterparts, and are frequently relegated to being mere inflated sex toys or male stand-ins, meant more to titillate male readers than reach out to a female demographic. That's kind of an intense way of putting this: we don't got lady writers so we don't got lady superheroes.

Following?

Brutalized and infantilized at every turn, female superheroes are neither considered to be as powerful as the “real” heroes, nor as interesting, while they are sexualized and forced into secondary roles. Beyond that, female characters in general are subjected to a level of brutality that would shock even the most hardened cynic. I’m not letting my daughter see that.

My first choice of feminist icon should be Wonder Woman, right? She is Wonder Woman, after all, and I freaking named my blog after her.

Actually created to be a feminist icon by the creative team of William and Elizabeth Marston in 1941, their stated goal was to give young girls strong female archetype. William Marston was quoted in The American Scholar, 1943 as saying, “Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power.” All well and good. Wonder Woman was to fight the Nazis, represent patriotic America. She kicked ass.

This goal, however, was not generally followed through in the comics. Certainly Wonder Woman is powerful, but perhaps a little too powerful. She’s not only an Amazonian Princess from a mystical island of warrior women, she also runs a Fortune 500 company under the name Diana Prince, and is one of the spearheads of the Justice League. She was a goddess for a while. She has the strength of 100 men, can run 80 mph, and she does all of this in a patriotic bathing-suit that only barely manages to cover her rippling abs.

Talk about hard to live up to.

In addition, she has a set of unbreakable gauntlets that can deflect bullets, a lasso of truth, and an invisible jet. Oh and a crown.

If you dig a little deeper, though, you’ll see that Wonder Woman’s problems are even more than just her frightening perfection. A foundational member of the Justice League, written to equal Superman and Batman, Wonder Woman was originally the League’s secretary. For serious. It was the only way they'd let her in. And far from being the superpowered action hero that the Marstons intended, Wonder Woman’s early years were spent mostly being tied up. It was such a common trope that there is now an entire online archive of old comics demarcating thebondage in old issues of Wonder Woman. (You're welcome.)

It’s not just Wonder Woman out there, though. There are other female superheroes, sidekicks, villains, and of course girlfriends and plucky reporters. But in all of these cases, the problems are the same. The women are not characters, by and large (see yesterday's article here). They're caricatures, propelled by their tits into a world of violence and hyper-aggressive male behavior, motivated purely by the male gaze.

Here’s the flip side: Batgirl, aka Barbara Gordon, aka Oracle. Also a DC character, she was introduced in 1967 to balance out the gender ratios of the Batman universe, and to make up for some earlier miss-steps regarding female characters.

Barbara Gordon, created by Gardner Fox and Carmine Infantino, was originally written as Commissioner Gordon’s daughter. Having grown up hearing all about Batman from her father, she decided to dress as a female Batman for a costume party, but along the way ended up rescuing Bruce Wayne from Killer Moth. She got a taste for the vigilante lifestyle, and decided to stick with it, even when Batman told her that she couldn’t fight because she was a woman. Barbara Gordon, it seemed, was one they finally got right.

In 1988, Alan Moore wrote The Killing Joke, a critically acclaimed serial wherein the Joker found an unsuited Barbara Gordon, and shot her. Seriously, it's a great arc, and one of the best superhero stories. Check it out. Anyway, the shot didn't kill her, but it did leave her paralyzed from the waist down.

More insulting, however, than the injury, though, was the way it was handled. You see, Babs was not the main character of this serial. She was incidental to the action, and thus her crippling injury and the massive effect it had on her life was tangential. She was barely mentioned. Batgirl got fridged.

And then.

She got a second act. Barbara Gordon did not stay down. The writing team of Kim Yale and John Ostrander was horrified by Gordon’s treatment, and decided to fix it. They rehabilitated her character into Oracle, an information-broker for the Bat family, who happened to be paraplegic. She learned to fight using only her upper body, and to live with her disability. Oracle appeared first in Suicide Squad #23, and was revealed to be Barbara Gordon in #38 of the same line. She continued to appear in comics, and eventually came to be Batman’s main source of information. She ended up running The Birds of Prey, her own superhero team, and mentoring the new Batgirl. It seemed like Barbara Gordon was finally the one character that fridging couldn’t put down.

In September of 2011 DC relaunched all of their properties: The New 52. You may have heard me ranting about how much I hate this before. Like, a lot. Well, most of that comes down to what they did to Babs: they pushed her story back to several months after her paralyzing accident. Except this time, she got to walk after.

You might be saying, so what? Good for her. She gets to walk again, isn't that great?

Nope.

It’s demeaning to imagine that Barbara Gordon, a woman who has clearly been through so much, and become so very strong through her experiences, has now been robbed of what made her the hero she is. She learned to not just deal with, but own her disability. She became stronger because of it. So to take that away? She’s been fridged all over again.

So what does all of this mean? Well, I think it comes down to the devaluation of women's bodies on the behalf of the writers. It's not that men don't get hurt or killed in comics, it's that it's treated differently. When the male heroes are downed, it's a thing. There is mourning. They make statements. The storyline matters and is hailed as groundbreaking. When a woman dies in a comic book, it's just another Tuesday. If she comes back, cool, if not, whatever.

I'm not saying everyone has this attitude, but it does seem to be implicit in the way women are treated. Starfire's body isn't her own, it's the audience's, so she will display it to the audience so they can admire. Barbara Gordon's body isn't her own, it's the writer's, his to maim and heal as he likes.

And Wonder Woman's body isn't her own either. It's everyone's. To tie up and objectify and make creepy porn of or fantasize about punching. It's not hers. It's ours.

Call me overinvested, but that is not a message I'm willing to let my daughter see.

|

| Big Barda deserved better. |